Yesterday I found myself in a dinner conversation with three other women, all in different stages of a relationship with a man: one recently married, one engaged, and the third in a long-term partnership. We began talking about whether each of us had changed, or planned to change, our names upon marriage. I felt my heart rate quicken a little when the subject came up, because this is a topic that brings up strong feelings for me, and for many other people.

As a young romantic, I used to doodle the name of my latest crush in my school notebook in flowery cursive. Occasionally, I would write, “Mrs. Melia ____“, filling in the blank with the last name of the object of my affection. I wanted to know how our names sounded together, and I took it for granted that one day, my dream guy would fill in that blank permanently.

Part of my expectation came from the fact that I didn’t like my last name, Dicker, at all when I was growing up. Other kids would snicker at it when they heard it for the first time. Some would even say with genuine disbelief, “Is that really your last name?” (I’m sure the Woodcocks and the Hardwicks of the modern world sympathize with me here.) I hoped that I’d get married early in life so I could take my husband’s name and make people quit it with the penis jokes, already.

But I didn’t end up getting married early in life. I got married at age 30, and by that time, I’d made peace with my last name. It felt comfortable, like a funky sweater that I’d worn awkwardly as a kid but had grown into as an adult. Most of my peers had matured enough that they didn’t need to stifle a laugh when I introduced myself. When the occasional douchebag at a party would say, “Haha, Dicker?” (yes, this actually happened in my 20’s), I’d just roll my eyes and reply, “Dude, I’ve heard ’em all,” before turning to find someone else to talk with.

By age 30, I’d established myself professionally and had worked hard to do so. I had made major personal sacrifices to co-found two nonprofit organizations. I’d put in many hours to build my byline as a freelance writer. I had done those things as Melia Dicker, and I didn’t want to destroy my credentials by changing my name. But still, I didn’t find the decision easy to make. The romantic part of me wanted to share a name with my husband to symbolize our becoming an official, lifelong team.

After I’d given it a lot of thought, I decided to keep my name, at least for the time being. The choice was half purposeful, half practical. Purposefully, I wanted to avoid being absorbed into my husband’s identity (the origin of women’s name-changing upon marriage is coverture, in which a woman’s legal rights were subsumed by her husband). Practically, “Melia Schwindaman” simply does not roll off the tongue. In my ideal world, Darren and I would combine our names to form a new one, but sadly, “Dicker-Schwindaman” and “Dickaman” sound pretty ri-dick-ulous. We jokingly call ourselves “The Schwindickermans” but would never legally impose such a mouthful on ourselves, and certainly not on our future children.

So, my husband remains Darren Schwindaman, and I’m still Melia Dicker. Together, we’re The Schwindickermans. We’re a team. And neither of us gave up a name that has defined us since the day we were born.

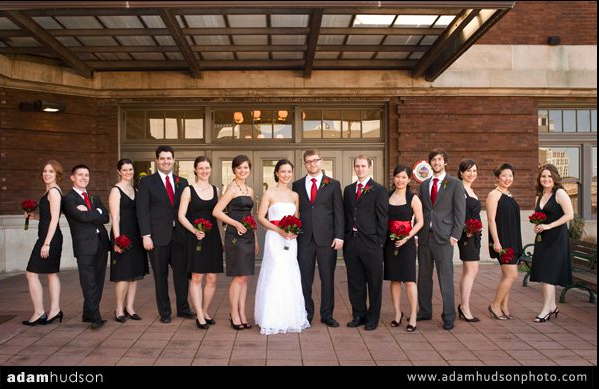

I want to be clear that my choice to keep my name doesn’t mean that I judge women who take their husband’s. I deeply respect my sister, Gill, and several of my closest friends, who thought carefully about their options before they decided to change their names. They acknowledged mixed feelings about it, and they recognized the emotional impact of saying goodbye to a name that they’d had for at least a couple of decades (Gill has written beautifully about how challenging this process was for her). They had their reasons: they liked their husband’s name better; they wanted to become a clear family unit; or they wanted to simplify matters for their future children. They didn’t change their names because that’s what women do when they get married.

What bothers me is the widespread expectation that women will take their husbands’ names. I could stomach the fact that 90 to 95 percent of women take their husbands names if I knew that it was a choice that they were making consciously and freely. But for many women and their husbands, it’s an action that’s taken for granted. It raises my blood pressure to know that 50 percent of 815 respondents in a 2011 survey believed that women should be legally required to take their husbands’ names (published in the journal Gender & Society, reported by LiveScience). What really sends me through the roof is a common response by survey participants when asked if it were OK for a man to take his wife’s last name. “They were incredulous,” said Brian Powell, one of the Indiana University sociologists behind the survey. “They would laugh at it. One quote was, ‘Sure, if he wants to be a woman.'” To me, seeing this kind of sexism in the 21st century is absolutely maddening.

There seems to be a resurgence of traditional practices in marriage even among those who consider themselves liberal. Over the past 10 years, it’s actually become less common for women to keep their own names than in previous years. The Huffington Post reported that the practice peaked in the 1990s at 23 percent and declined to 18 percent in the 2000s. Last year, in a survey of 19,000 women by TheKnot.com, only 8 percent reported keeping their own names. (Granted, brides who use TheKnot.com may be more traditional than those who don’t.)

At the same time, however, more women are writing about their decision to keep their names, more couples are combining their last names to form a new one, and more men are stepping up and taking their wives’ last names. In fact, a California man fought successfully in 2008 for a new state law that guarantees the right of either partner in a marriage or domestic partnership to choose the name they prefer. Stunningly, there are fewer than 10 states with laws like this.

Before I read up on the subject, I was only partially convinced that keeping my name was right for me. Now, I’m sure of it. As Anna Quindlen writes in one of my favorite essays, “The name is mine.”

Changing your name is a choice. Please don’t assume that a woman will change her name when she gets married, and certainly don’t assume that she should. If you believe that women and men should have equal rights, then you can’t expect a woman to take a man’s name just because she marries him. No one would expect the reverse of a man.

Last night at dinner, as I felt myself tensing up during the name-change conversation, I began to relax when I learned that all three women at the table had given plenty of thought to what they would do with their names upon marriage and why. They had reasons that guided their decisions, and they had conflicting feelings about them. It didn’t matter as much to me what these women had decided as it did to know that they’d recognized their power to make a choice in the first place, a choice that was right for them.

Tags: 4 Comments